Thursday, 19 April 2007

Recuperation& Detournement

Recuperation: "To survive, the spectacle must have social control. It can recuperate a potentially threatening situation by shifting ground, creating dazzling alternatives- or by embracing the threat, making it safe and then selling it back to us"- Larry Law, from The Spectacle- The Skeleton Keys, a 'Spectacular Times pocket book.

"Ha! You think it's funny? Turning rebellion into money?" -- The Clash, (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais.

Recuperation is the process by which the spectacle takes a radical or revolutionary idea and repackages it as a saleable commodity.

An example of recuperation, it could be argued, was the 1989 Situationist exhibition staged in Paris, Boston, and at the ICA gallery in London's Mall, wherein both original situationist manifestos, and contemporary Pro-Situ influenced works (records, fanzines, samizdat-style leaflets and propaganda) were presented in a way that reinforced the prestige of the art establishment, for passive public consumption. This event of course contrasts sharply to the occasion when the Situationist International gave a presentation at the ICA themselves, which famously ended when an audience member asked the group "what is situationism?" to which Guy Debord responded "we are not here to answer cuntish questions" before marching off to the bar. Although all would agree that a lot of water has gone under the bridge since 1989 with regard to the image of the SI in the media, another example that might be cited would be the exhibition and other events on "The SI and After" that were staged by the Aquarium art gallery in London in 2003.

A longer-lasting example, it could be argued, would be the "Hacienda" nightclub in Manchester (1982-1997). Highly commercially successful, this was named by its owner, British music-industry businessman Tony Wilson, after a reference in the 1953 work "Formulary for a New Urbanism" by Ivan Chtcheglov. Millionaire Wilson's company Factory Records was one of the sponsors of the 1989 ICA exhibition (along with Beck's beer). Later, in 1996, he allowed a conference on the SI to be staged at the Hacienda night-club. Veteran Situationist-influenced critics of recuperation were not surprised to learn that Wilson had invested funds in collecting Situationist-linked artworks, including Debord's "Psychogeographical Map of Paris" (1953), some of which he allowed to be shown in public at the Aquarium event in 2003. An index of the financial astuteness of such speculation is the fact that there are now dealers in artworks and fine books who count Situationist-linked works among their specialities.

DETOURNEMENT

One could view detournement as forming the opposite side of the coin to 'recuperation' (where radical ideas and images become safe and commodified), in that images produced by the spectacle get altered and subverted so that rather than supporting the status quo, their meaning becomes changed in order to put across a more radical or oppositionist message.

"Ha! You think it's funny? Turning rebellion into money?" -- The Clash, (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais.

Recuperation is the process by which the spectacle takes a radical or revolutionary idea and repackages it as a saleable commodity.

An example of recuperation, it could be argued, was the 1989 Situationist exhibition staged in Paris, Boston, and at the ICA gallery in London's Mall, wherein both original situationist manifestos, and contemporary Pro-Situ influenced works (records, fanzines, samizdat-style leaflets and propaganda) were presented in a way that reinforced the prestige of the art establishment, for passive public consumption. This event of course contrasts sharply to the occasion when the Situationist International gave a presentation at the ICA themselves, which famously ended when an audience member asked the group "what is situationism?" to which Guy Debord responded "we are not here to answer cuntish questions" before marching off to the bar. Although all would agree that a lot of water has gone under the bridge since 1989 with regard to the image of the SI in the media, another example that might be cited would be the exhibition and other events on "The SI and After" that were staged by the Aquarium art gallery in London in 2003.

A longer-lasting example, it could be argued, would be the "Hacienda" nightclub in Manchester (1982-1997). Highly commercially successful, this was named by its owner, British music-industry businessman Tony Wilson, after a reference in the 1953 work "Formulary for a New Urbanism" by Ivan Chtcheglov. Millionaire Wilson's company Factory Records was one of the sponsors of the 1989 ICA exhibition (along with Beck's beer). Later, in 1996, he allowed a conference on the SI to be staged at the Hacienda night-club. Veteran Situationist-influenced critics of recuperation were not surprised to learn that Wilson had invested funds in collecting Situationist-linked artworks, including Debord's "Psychogeographical Map of Paris" (1953), some of which he allowed to be shown in public at the Aquarium event in 2003. An index of the financial astuteness of such speculation is the fact that there are now dealers in artworks and fine books who count Situationist-linked works among their specialities.

DETOURNEMENT

One could view detournement as forming the opposite side of the coin to 'recuperation' (where radical ideas and images become safe and commodified), in that images produced by the spectacle get altered and subverted so that rather than supporting the status quo, their meaning becomes changed in order to put across a more radical or oppositionist message.

Sunday, 15 April 2007

Essay Plan 15/04/07

Introduction - talk different kids of revolutions(e.g. political, cultural, artistic), and how they are linked.

talk about Russian Revolution and it's relationship with art and set out the ideas explored later. (N.b. THIS I AM STILL FINDING HARD TO DISTILL INTO A BITE SIZED PIECE. IT'S A HUGE SUBJECT WHICH EVOLVED OVER DECADES. WHAT DO DO HERE?). Agitprop etc. zzzzzzz One interesting thing is the aesthetics. This was some of the most influential graphic design in it's history. Photomontage was also used to great effect by Rodchenko and El Lissitsky.

Revolutions are initially subversive, but then there is the following counter revolution. This was the case with the Russian Revolution, which started as a peoples revolution, but over time the people were suppressed by Stalin.

Revolution - An allegory - i.e A metaphor: George Orwell “Animal Farm” USE QUOTES

Situationists and 1968 Student Revolution in Paris. This can link into RECUPERATION - how art can be subverted, and re-used in different contexts or exploited for money.e.g. -The Nina Simone article which will provide a great quote. see also situationist bit, Recuperation & Detournement. - LOTS OF MATERIAL IN SITUATIONIST SECTION

No Logo, Adbusters, Subvertising. Cultural Resistance. Commercial Revolution, branding, contemporary stuff "What Barry Says", Nike etc. lots of examples and Illustrations.

talk about Russian Revolution and it's relationship with art and set out the ideas explored later. (N.b. THIS I AM STILL FINDING HARD TO DISTILL INTO A BITE SIZED PIECE. IT'S A HUGE SUBJECT WHICH EVOLVED OVER DECADES. WHAT DO DO HERE?). Agitprop etc. zzzzzzz One interesting thing is the aesthetics. This was some of the most influential graphic design in it's history. Photomontage was also used to great effect by Rodchenko and El Lissitsky.

Revolutions are initially subversive, but then there is the following counter revolution. This was the case with the Russian Revolution, which started as a peoples revolution, but over time the people were suppressed by Stalin.

Revolution - An allegory - i.e A metaphor: George Orwell “Animal Farm” USE QUOTES

Situationists and 1968 Student Revolution in Paris. This can link into RECUPERATION - how art can be subverted, and re-used in different contexts or exploited for money.e.g. -The Nina Simone article which will provide a great quote. see also situationist bit, Recuperation & Detournement. - LOTS OF MATERIAL IN SITUATIONIST SECTION

No Logo, Adbusters, Subvertising. Cultural Resistance. Commercial Revolution, branding, contemporary stuff "What Barry Says", Nike etc. lots of examples and Illustrations.

Propaganda

Link for wikipedia page

Russian revolutionaries of the 19th and 20th centuries distinguished two different aspects covered by the English term propaganda. Their terminology included two terms: Russian: агитация (agitatsiya), or agitation, and Russian: пропаганда, or propaganda, see agitprop (agitprop is not, however, limited to the Soviet Union, as it was considered, before the October Revolution, to be one of the fundamental activity of any Marxist activist; this importance of agit-prop in Marxist theory may also be observed today in Trotskyist circles, who insist on the importance of leaflet distribution).

Soviet propaganda meant dissemination of revolutionary ideas, teachings of Marxism, and theoretical and practical knowledge of Marxist economics, while agitation meant forming favorable public opinion and stirring up political unrest. These activities did not carry negative connotations (as they usually do in English) and were encouraged. Expanding dimensions of state propaganda, the Bolsheviks actively used transportation such as trains, aircraft and other means.

Josef Stalin's regime built the largest fixed-wing aircraft of the 1930s, Tupolev ANT-20, exclusively for this purpose. Named after the famous Soviet writer Maxim Gorky who had recently returned from fascist Italy, it was equipped with a powerful radio set called "Voice from the sky", printing and leaflet-dropping machinery, radiostations, photographic laboratory, film projector with sound for showing movies in flight, library, etc. The aircraft could be disassembled and transported by railroad if needed. The giant aircraft set a number of world records.

Russian revolutionaries of the 19th and 20th centuries distinguished two different aspects covered by the English term propaganda. Their terminology included two terms: Russian: агитация (agitatsiya), or agitation, and Russian: пропаганда, or propaganda, see agitprop (agitprop is not, however, limited to the Soviet Union, as it was considered, before the October Revolution, to be one of the fundamental activity of any Marxist activist; this importance of agit-prop in Marxist theory may also be observed today in Trotskyist circles, who insist on the importance of leaflet distribution).

Soviet propaganda meant dissemination of revolutionary ideas, teachings of Marxism, and theoretical and practical knowledge of Marxist economics, while agitation meant forming favorable public opinion and stirring up political unrest. These activities did not carry negative connotations (as they usually do in English) and were encouraged. Expanding dimensions of state propaganda, the Bolsheviks actively used transportation such as trains, aircraft and other means.

Josef Stalin's regime built the largest fixed-wing aircraft of the 1930s, Tupolev ANT-20, exclusively for this purpose. Named after the famous Soviet writer Maxim Gorky who had recently returned from fascist Italy, it was equipped with a powerful radio set called "Voice from the sky", printing and leaflet-dropping machinery, radiostations, photographic laboratory, film projector with sound for showing movies in flight, library, etc. The aircraft could be disassembled and transported by railroad if needed. The giant aircraft set a number of world records.

Saturday, 14 April 2007

May 1968 - Student Riots Paris

The header above is a link to the wikipedia page.

It is difficult to pigeonhole the politics of the students who sparked the events of May 1968, much less of the hundreds of thousands who participated in them. There was, however, a strong strain of anarchism, particularly in the students at Nanterre. While not exhaustive, the following graffiti give a sense of the millenarian and rebellious spirit, tempered with a good deal of verbal wit, of the strikers (the anti-work graffiti shows the considerable influence of the situationist movement):

It is difficult to pigeonhole the politics of the students who sparked the events of May 1968, much less of the hundreds of thousands who participated in them. There was, however, a strong strain of anarchism, particularly in the students at Nanterre. While not exhaustive, the following graffiti give a sense of the millenarian and rebellious spirit, tempered with a good deal of verbal wit, of the strikers (the anti-work graffiti shows the considerable influence of the situationist movement):

Lisez moins, vivez plus.

Read less, live more.

L'ennui est contre-révolutionnaire.

Boredom is counterrevolutionary.

Pas de replâtrage, la structure est pourrie.

No replastering, the structure is rotten.

Nous ne voulons pas d'un monde où la certitude de ne pas mourir de faim s'échange contre le risque de mourir d'ennui.

We want nothing of a world in which the certainty of not dying from hunger comes in exchange for the risk of dying from boredom.

Ceux qui font les révolutions à moitié ne font que se creuser un tombeau.

Those who make revolutions by halves do but dig themselves a grave.

On ne revendiquera rien, on ne demandera rien. On prendra, on occupera.

We will claim nothing, we will ask for nothing. We will take, we will occupy.

Plebiscite : qu'on dise oui qu'on dise non il fait de nous des cons.

Plebiscite: Whether we say yes or no, it makes chumps of us.

Depuis 1936 j'ai lutté pour les augmentations de salaire. Mon père avant moi a lutté pour les augmentations de salaire. Maintenant j'ai une télé, un frigo, une VW. Et cependant j'ai vécu toujours la vie d'un con. Ne négociez pas avec les patrons. Abolissez-les.

Since 1936 I have fought for wage increases. My father before me fought for wage increases. Now I have a TV, a fridge, a Volkswagen. Yet my whole life I've been a chump. Don't negotiate with the bosses. Abolish them.

Le patron a besoin de toi, tu n'as pas besoin de lui.

The boss needs you, you don't need him.

Travailleur: Tu as 25 ans mais ton syndicat est de l'autre siècle.

Worker: You are 25, but your union is from the last century.

Veuillez laisser le Parti communiste aussi net en sortant que vous voudriez le trouver en y entrant.

Please leave the Communist Party as clean on leaving as you would like to find it on entering.

Soyez réalistes, demandez l'impossible.

Be realistic, ask for the impossible.

On achète ton bonheur. Vole-le.

They buy your happiness. Steal it.

Sous les pavés, la plage !

Beneath the paving stones - the beach!

Ni Dieu ni maître !

Neither God nor master!

Godard : le plus con des suisses pro-chinois !

Godard: the damnest of all the pro-Chinese Swiss fools!

Soyons cruels !

Let's be cruel!

Comment penser librement à l'ombre d'une chapelle ?

How can one think freely in the shadow of a chapel?

À bas la charogne stalinienne ! À bas les groupuscules récupérateurs !

Down with the Stalinist carcass! Down with the recuperator cells!

Vivre sans temps mort - jouir sans entraves

Live without dead time [time of boredom, time at work] - enjoy without chains.

Il est interdit d'interdire.

It is forbidden to forbid.

Et cependant tout le monde veut respirer et personne ne peut respirer et beaucoup disent " nous respirerons plus tard ". Et la plupart ne meurent pas car ils sont déjà morts.

Meanwhile everyone wants to breathe and nobody can breathe and many say, "We will breathe later". And most of them don't die because they are already dead.

Dans une société qui a aboli toute aventure, la seule aventure qui reste est celle d'abolir la société.

In a society that has abolished all adventures, the only adventure left is to abolish society.

L'émancipation de l'homme sera totale ou ne sera pas.

The liberation of humanity will be total or it will not be.

La révolution est incroyable parce que vraie.

The revolution is unbelievable because it's real.

Je suis venu. J'ai vu. J'ai cru.

I came. I saw. I believed. [Mimics Veni, vidi, vici.]

Cours, camarade, le vieux monde est derrière toi !

Run, comrade, the old world is behind you!

Il est douloureux de subir les chefs, il est encore plus bête de les choisir.

It's painful to suffer the bosses; it's even stupider to pick them.

Un seul week-end non révolutionnaire est infiniment plus sanglant qu'un mois de révolution permanente.

A single nonrevolutionary weekend is infinitely more bloody than a month of permanent revolution.

Le bonheur est une idée neuve.

Happiness is a new idea. [To be happy is a new notion.]

La culture est l'inversion de la vie.

Culture is the inversion of life.

La poésie est dans la rue.

Poetry is in the street.

L'art est mort, ne consommez pas son cadavre.

Art is dead, don't consume its corpse.

L'alcool tue. Prenez du L.S.D.

Alcohol kills. Take LSD.

Debout les damnés de l'Université.

Arise, you wretched of the University. [Mimics The Internationale.]

Même si Dieu existait il faudrait le supprimer.

Even if God existed, it would be necessary to abolish him. [Paraphrases Bakunin.]

SEXE : C'est bien, a dit Mao, mais pas trop souvent.

SEX: It's good, says Mao, but not too often.

Je t'aime ! Oh ! dites-le avec des pavés !

I love you! Oh, say it with paving stones!

Camarades, l'amour se fait aussi en Sciences-Po, pas seulement aux champs.

Comrades, love is being made at Sciences-Po [a prestigious academic institution of political science] too, not just in the fields.

Mort aux vaches !

Death to the cows! [Cops, police.]

Travailleurs de tous les pays, amusez-vous !

Workers of the world, have fun! [Mimics "Workers of the world, unite!"]

Pouvoir à l'Imagination

Power to the Imagination.

: 'sois jeune - tais-toi!

Be young - shut up!

: "Usines, Universites, Union"

Factories, Universities, Union

: 'Je participe :Tu participes :il participe :nous participons :vous participez :ils profitent

I take part

you take part

he takes part

we take part

you all take part

they profit.

Situationists

The header is a live link to wikipedia page

While the entire history of the Situationists was marked by their impetus to revolutionize life, the split was characterised by Vaneigem (of the French section), and by many subsequent critics, as marking a transition in the French group from the Situationist view of revolution possibly taking an "artistic" form to an involvement in "political" agitation. Asger Jorn continued to fund both groups with the proceeds of his works of art.

One way or another, the currents which the SI took as predecessors saw their purpose as involving a radical redefinition of the role of art in the twentieth century. The Situationists themselves took a dialectical viewpoint, seeing their task as superseding art, abolishing the notion of art as a separate, specialized activity and transforming it so it became part of the fabric of everyday life. From the Situationist's viewpoint, art is revolutionary or it is nothing. In this way, the Situationists saw their efforts as completing the work of both Dada and surrealism while abolishing both. Still, the Situationists answered the question "What is revolutionary?" differently at different times.

MAY 1968 - Student revolution

The SI's part in the revolt of 1968 has often been overemphasised. They were a very small group, but were expert self-propagandists, and their slogans appeared daubed on walls throughout Paris at this time.

Influence

Situationist ideas have continued to echo profoundly through many aspects of culture and politics in Europe and the USA. Even in their own time, with limited translations of their dense theoretical texts, combined with their very successful self-mythologisation, the term 'situationist' was often used to refer to any rebel or outsider, rather than to a body of surrealist-inspired Marxist critical theory. As such, the term 'situationist' and those of 'spectacle' and 'detournement' have often been decontextualised and recuperated.

Most recently, more politically heterogeneous radical groups such as Reclaim the Streets and Adbusters have respectively, seen themselves as 'creating situations' or practicing detournement on advertisements.

In cultural terms, the SI's influence has been even greater, if more diffuse. The list of cultural practices which claim a debt to the SI is almost limitless, but there are some prominent examples:

Situationist ideas exerted a strong influence on the design language of the early punk rock phenomenon of the 1970s, for example. To a significant extent this came about due to the adoption of the style and aesthetics and sometimes slogans employed by the Situationists (though these latter were often second hand, via English pro-Situs such as King Mob and Jamie Reid). Other musical artists have attempted to more directly include buzzwords from the SI's critical theory into their lyrics, such as Swedish hardcore band Refused, The International Noise Conspiracy and the Welsh rock band The Manic Street Preachers.

Situationist practices allegedly continue to influence underground street artists such as gHOSTbOY, Banksy, Borf, and Mudwig, whose artistic interventions and subversive practice can be seen on advertising hoardings, street signs and walls throughout Europe and The United States.

While the entire history of the Situationists was marked by their impetus to revolutionize life, the split was characterised by Vaneigem (of the French section), and by many subsequent critics, as marking a transition in the French group from the Situationist view of revolution possibly taking an "artistic" form to an involvement in "political" agitation. Asger Jorn continued to fund both groups with the proceeds of his works of art.

One way or another, the currents which the SI took as predecessors saw their purpose as involving a radical redefinition of the role of art in the twentieth century. The Situationists themselves took a dialectical viewpoint, seeing their task as superseding art, abolishing the notion of art as a separate, specialized activity and transforming it so it became part of the fabric of everyday life. From the Situationist's viewpoint, art is revolutionary or it is nothing. In this way, the Situationists saw their efforts as completing the work of both Dada and surrealism while abolishing both. Still, the Situationists answered the question "What is revolutionary?" differently at different times.

MAY 1968 - Student revolution

The SI's part in the revolt of 1968 has often been overemphasised. They were a very small group, but were expert self-propagandists, and their slogans appeared daubed on walls throughout Paris at this time.

Influence

Situationist ideas have continued to echo profoundly through many aspects of culture and politics in Europe and the USA. Even in their own time, with limited translations of their dense theoretical texts, combined with their very successful self-mythologisation, the term 'situationist' was often used to refer to any rebel or outsider, rather than to a body of surrealist-inspired Marxist critical theory. As such, the term 'situationist' and those of 'spectacle' and 'detournement' have often been decontextualised and recuperated.

Most recently, more politically heterogeneous radical groups such as Reclaim the Streets and Adbusters have respectively, seen themselves as 'creating situations' or practicing detournement on advertisements.

In cultural terms, the SI's influence has been even greater, if more diffuse. The list of cultural practices which claim a debt to the SI is almost limitless, but there are some prominent examples:

Situationist ideas exerted a strong influence on the design language of the early punk rock phenomenon of the 1970s, for example. To a significant extent this came about due to the adoption of the style and aesthetics and sometimes slogans employed by the Situationists (though these latter were often second hand, via English pro-Situs such as King Mob and Jamie Reid). Other musical artists have attempted to more directly include buzzwords from the SI's critical theory into their lyrics, such as Swedish hardcore band Refused, The International Noise Conspiracy and the Welsh rock band The Manic Street Preachers.

Situationist practices allegedly continue to influence underground street artists such as gHOSTbOY, Banksy, Borf, and Mudwig, whose artistic interventions and subversive practice can be seen on advertising hoardings, street signs and walls throughout Europe and The United States.

Friday, 13 April 2007

Alexander Rodchenko

Wikipedia page here

Rodchenko was one of the most versatile Constructivist and Productivist artists to emerge after the Russian Revolution. He worked as a painter and graphic designer before turning to photomontage and photography. His photography was socially engaged, formally innovative, and opposed to a painterly aesthetic. Concerned with the need for analytical-documentary photo series, he often shot his subjects from odd angles - usually high above or below - to shock the viewer and to postpone recognition. He wrote: "One has to take several different shots of a subject, from different points of view and in different situations, as if one examined it in the round rather than looked through the same key-hole again and again."

Rodchenko's designs arer aften plundered commercially by the music industry, most recently by Franz Ferdinand

Revolutions & Russia

Notes and quotes from "Modernism" (Richard Weston)

Aesthetic and political revolution were inextricably linked in Russia, and both were fermenting well before the 'then days that changed the world' brought the overthrow of the Tsar and bourgeois culture in October 1917.

P142

The European avant-garde: Russian Futurism was launched in 1912 by the three Burliuk brothers with the manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste. They got together with like-minded artists and poets, convincing a young Vladimir Mayakovsky he had poetic taletnt, and collaborating with Mikhail Larinov and Natalia Goncharova. the Burliuks organized the 'Jack of Diamonds" exhibition which ran from December 1910 to January 1911. This was the first landmark Modernist show in Russia. This then brought together the Moscow and St petersberg Circles, and marked the emergence of Olga Rozanova and Vladimir Tatlin.

Many of the artists practiced more then one discipline and the visual arts and literature were so closely linked as to be almost inseparable.

Kasimir Malevich exhibited his new art in the '0.10' exhibition in Petrograd, which was dubbed the 'Last Futurist Exhibition', republishing his manifesto in 1916 under the title From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: the New Pictorial Realism, staking his claim to have invented abstract art:

“All painting of the past and prior to suprematism (sculture, verbal art, music) was in thrall to the form of nature and awiated it's liberation in order to speak it's own language”

P145

Malevich 'Black Square' 1915 (see image) - This became his symbol of artistic revolution. Malevich believed that his art was the first fruits of new age in which form would finally triumph over nature and brute material, and where intuition, not reason, was the only guide. he was an inspiring figure, and other artists - Kliun, Rozanova, Popova, Puni and his wife Boguslavkaya and later El Lissitzky - were not slow to rally to the supremitist cause.

1915 also marked the arrival of Vladimir Tatlin.

Tatlin was a key figure in the move from art towards design and 'contruction': What interested him were real materials in real space. In Many ways tatlin was Malevich's anthisis. The opposition between dematerialisation and 'truth to materials' has formed a conspicuous and recurring theme of Modernist art - De Stijl and Cubism presented similar polarities - and finding it's roots, ultimately, in the oppositiobn between idealist and materialist philosophies, between religion and "the world", between spirit and the body. In Russia, where the mystical traditions of Orthodoz Church were about to be challaneged by the revolutionary materialism of karl marx, the opposition not surprisingly took a variety of extreme forms.

P146

Tatlin later observed that “the political events of 1917 were prefigured in our art in 1914”, and as artistic revolutionaries who had conqured exhausted bougeois traditions, they welcomed the challange of forginga revolutionary, proletarian art.

Anatoly Lunarcharsky, the Commisar of Education and Culture only valued the avant-garde's support becuase no-one else would collaborate with him.

Red Army & Agitprop, used to win converts to the Bloshevik cause. Soviet Modernists, unlike their European counterparts faced the challenge of helping to sell the Revolution to a vast polulation, many of whom were illiterate. They used Illustrated broadsheets and graphic designs in newspapers.

Rosta posters, Agitprop trains.

CONSTRUCTIVISM (from oxford univerity press)

(i) Formation, 1914–21.

The technique of constructing sculpture from separate elements, as opposed to modelling or carving, was developed by Pablo Picasso in 1912, extending the planar language of Cubism into three dimensions. This method was elaborated in Russia, initially by Vladimir Tatlin from 1914 onwards and then by his many followers, who, like him, made abstract sculptures that explored the textural and spatial qualities of combinations of contemporary materials such as metal, glass, wood and cardboard, as in Tatlin’s Selection of Materials (1914; untraced) and Corner Counter-Relief (1914–15; untraced; see Lodder, figs 1.12–13).

Russian artists did not begin to call their work ‘constructions’ and themselves ‘constructivists’ until after the Revolution of 1917. Coining the latter term, the First Working Group of Constructivists, also known as the Working Group of Constructivists, was set up in March 1921 within Inkhuk (Institute of Artistic Culture) in Moscow. The group comprised Aleksey Gan (1893–1942), aleksandr Rodchenko, varvara Stepanova, Konstantin Medunetsky, Karl Ioganson (Karel Johansen; c. 1890–1929) and the brothers Georgy Stenberg and Vladimir Stenberg. These artists had come together during theoretical discussions concerning the distinction between composition and construction as principles of artistic organization, which were conducted within the Working Group of Objective Analysis at Inkhuk between January and April 1921. ‘Construction’ was seen to have connotations of technology and engineering and therefore to be characterized by economy of materials, precision, clarity of organization and the absence of decorative or superfluous elements.

In order to give their work the quality of ‘construction’, the artists increasingly renounced abstract painting in favour of working with industrial materials in space. This was epitomized by the Constructivists’ contributions to the Second Spring Exhibition of Obmokhu (Society of Young Artists), also known as the Third Exhibition of Obmokhu, which opened on 22 May 1921 (see Lodder, figs 2.15–16). The sculptures they showed displayed a strong commitment to the materials and forms of contemporary technology. The Stenbergs, for instance, created skeletal forms from materials such as glass, metal and wood, evoking engineering structures such as bridges and cranes, as in Georgy Stenberg’s Spatial Construction/KPS 51 NXI (1921; untraced; reconstruction, 1973; Cologne, Gal. Gmurzynska). Rodchenko showed a series of hanging constructions based on mathematical forms; they consisted of concentric shapes cut from a single plane of plywood, rotated to create a three-dimensional geometric form that is completely permeated by space, for example Oval Hanging Construction (1920–21; New York, MOMA).

In their programme of 1 April 1921, written by Gan, the Constructivists emphasized that they no longer saw an autonomous function for art and that they wished to participate in the creation of a visual environment appropriate to the needs and values of the new Socialist society: ‘Taking a scientific and hypothetical approach to its task, the group asserts the necessity to fuse the ideological component with the formal component in order to achieve a real transition from laboratory experiments to practical activity’ (1990 exh. cat., p. 67). They envisaged their work as ‘intellectual production’, proclaiming that their ideological foundation was ‘scientific communism, based on the theory of historical materialism’. They intended to attain what they termed ‘the communistic expression of material structures’ by organizing their work according to the three principles of tektonika (or tectonics, which derives from the principles of Communism and the functional use of industrial material, i.e. the politically and socially appropriate use of industrial materials with regard to a given purpose), konstruktsiya (or construction, the process of organizing this material), and faktura (the choice of material and its appropriate treatment). They also proposed to establish links with committees in charge of manufacturing and to conduct an intensive propaganda campaign of exhibitions and publications.

This artistic attitude was a product of the Utopian atmosphere generated by the Revolution and the specific conditions of the Civil War period (1918–21). After 1917, industry and the machine came to be seen as the essential characteristics of the working class and hence of the new Communist order. In practical terms, industrial development was also regarded by the state authorities as the key to political and social progress. Hence, the machine was both metaphor for the new culture under construction and the practical means to rebuild the economy as a prelude to establishing Communism. Moreover, the government fostered the debate concerning the role of art in industry, i.e. Production art (Rus. proizvodstvennoye iskusstvo; also known as Productivism), to which critics such as Osip Brik and Nikolay Punin contributed, arguing that the bourgeois distinction between art and industry should be abolished and that art should be considered as merely another aspect of manufacturing activity. The artists themselves had been encouraged to believe they had a wider public role to play by their participation in the many official commissions to execute such propaganda tasks as decorating Russian cities for the Revolutionary festivals and designing agitational and educational posters. During the chaotic Civil War period, the avant-garde had also helped to run artistic affairs on behalf of the government and seemed to have become a vehicle for expressing the Communist Party’s political objectives. The utilitarian ethos of Constructivism was a logical extension of this close identification between avant-garde art and social and political progress.

The Constructivists’ experiments were more directly stimulated by Tatlin’s extraordinary model for a Monument to the Third International, exhibited in Petrograd (now St Petersburg) in November 1920 and in Moscow in December 1920 (destr.; see fig.). The monument was conceived as a working building, an enormous skeletal apparatus a third higher than the Eiffel Tower, enclosing three rotating volumes intended to house the executive, administrative and propaganda offices of the Comintern. Resembling a huge functioning machine made of iron beams and glass, the tower demonstrated the power of the machine aesthetic as a symbol of revolutionary objectives. Tatlin declared that he was restoring the essential unity of painting, sculpture and architecture, ‘combining purely artistic forms with utilitarian intentions… The fruits of this are models which give rise to discoveries serving the creation of a new world and which call upon producers to control the forms of the new everyday life’ (Bann, p. 14).

© Oxford University Press 2007

How to cite Grove Art Online

(ii) Achievements, 1922 onwards.

In 1922 Constructivism was consolidated, with the first practical realizations of the Constructivists’ impulse to extend the formal vocabulary of earlier artistic experiments into concrete design projects. Other artists embraced the group’s ideas, including lyubov’ Popova, Gustav Klucis, Anton Lavinsky (1893–1968), the painter and architect Aleksandr Vesnin and the architect moisey Ginzburg. Moreover, Gan elaborated and disseminated the Constructivist programme in his book Konstruktivizm (Tver’, 1922) and in various articles. Initially, the theatre served as a crucible for developing an appropriate visual environment to express the new way of life. The first Constructivist stage set was Popova’s design for Vsevolod Meyerhold’s production of Fernand Crommelynck’s farce The Magnanimous Cuckold, which opened on 25 April 1922 (see Lodder, figs 5.30, 31, 33). The mill in which the action is set became a multi-levelled skeletal apparatus of platforms, revolving doors, ladders, scaffolding and wheels that rotated at differing speeds at particularly intense moments during the play. The traditional costumes were replaced by overalls or production clothing ( prozodezhda) devised to facilitate the actors’ movements, which were based on biomechanics (a combination of acrobatics and stylized gestures inspired by robots and the commedia dell’arte). This event was followed by Stepanova’s set for Meyerhold’s production of Sukhovo-Kobylin’s Smert’ Tarelkina (‘The death of Tarelkin’; 24 Nov 1922), comprising a series of separate apparatuses constructed from standard-sized wooden planks, painted white, and by Vesnin’s set for the Kamerny Theatre’s production of G. K. Chesterton’s The Man who Was Thursday on 6 December 1923, which was a far more complex and architectural skeletal construction, evoking the modern city through its incorporation of specific urban elements such as scaffolding, conveyor belts, lift-shafts, steps, posters and neon signs.

The urge to create three-dimensional objects of direct social utility resulted in a number of designs for temporary agitational structures, such as portable and sometimes collapsible kiosks (e.g. Klucis’s propaganda stands of 1922, Gan’s folding street sales stand of c. 1922–3 and Lavinsky’s sales kiosk for the State Publishing House, 1924). The use of bold colours and simple geometric forms in such projects foreshadowed Rodchenko’s Workers’ Club, made for the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes held in Paris in 1925 and perhaps the most complete expression of the Constructivists’ design methodology. Workers’ clubs were seen as important new institutions, on political grounds (for inculcating the new values of Communism) as well as educationally, culturally and socially (replacing the traditional role of the Church). Rodchenko standardized the component elements of the furniture and observed strict economy in terms of space, material and production methods. The chairs, for example, comprised three uprights (two rods in front and a wider plank behind) attached at the top by an open semicircular band to provide arms, in the middle by a solid semicircular seat and at the base by three rods. Made of wood, a cheap and plentiful material in Russia, the furniture answered the problems of contemporary cramped living conditions, so that certain items were space-saving and collapsible for easy storage (e.g. folding tribune, screen, display board and bench).

The Constructivists produced some of their most innovative work in graphic design. Rodchenko, for example, conceived striking layouts and covers for avant-garde magazines such as Kino-fot (1922), Lef (1923–5) and Novy Lef (1927–8), for cinema posters and magazines and for advertising images of wider circulation, such as his poster Books for Every Field of Knowledge (1925; Moscow, Rodchenko Archv; see Rodchenko, aleksandr, fig. 2). These were often photomontages, combining bold typography and abstract design with cut-out photographic elements. As the product of a mechanical process, the photograph complemented the Constructivists’ commitment to technology, while conforming to the Communist Party’s stated preference for realistic and legible images accessible to the masses.

Generally, however, practical implementation of Constructivist ideas was very slow and sporadic. Industry had been decimated following almost seven years of conflict, and those factories that had survived were not sufficiently progressive to accommodate the new type of designer. In addition, the small-scale private enterprises set up under the provisions of NEP (New Economic Policy), implemented in 1921, were run by entrepreneurs known as Nepmen, who tended to be hostile to the geometric austerity of Constructivist designs. The government was keen to harness art to improve the quality of industrial production, but it encouraged the more traditional approach of applied art while sponsoring a return to realism in painting and sculpture. Constructivism was thus spurned by the Party, the working class and the new Soviet bourgeoisie (the Nepmen), who alone had the financial potential to become art patrons. The only area in which the Constructivists did establish a productive working relationship with any specific industrial enterprise was in the field of textile design. Popova and Stepanova produced many designs that were mass-produced by the First State Textile Printing Factory between late 1923 and 1924. They rejected traditional floral patterns in favour of economical combinations of one or more colours and simple geometric forms, as in Popova’s Textile Design (1924; priv. col., see Lodder, plate X).

The extension of Constructivist ideas into the area of architecture was primarily the work of the Vesnin brothers (Aleksandr, Leonid, and Viktor) and of Moisey Ginzburg, who in order ot promote their ideas set up Osa (Association of Contemporary Architects; 1925–30) in December 1925 and the journal Sovremennaya arkhitektura. The Vesnins’ Palace of Labour project (1922–23) for Moscow and their design for the Leningrad Pravda building (1924) established a distinct architectural vocabulary that had become subsumed within that of the International Style by the time its first buildings, such as Ginzburg’s Gosstrakh appartment block for Moscow (1926), were erected.

Alongside these practical activities, the Constructivists formulated and elaborated their design methodology within VkhUTEMAS (Higher Artistic and Technical Workshops), set up at the end of 1920 to train highly qualified master artists for industry. Of particular importance for developing Constructivist ideas were the basic course and the woodworking and metalworking faculty, the latter directed by Rodchenko. The teaching staff also included Stepanova, Vesnin, Klucis, Tatlin and el Lissitzky, whose work took on a more Constructivist character following his return from the West in 1925. At the school, a new generation of artists were being trained to be engineer-constructors or artist-constructors, who would fuse artistic skills with a specialized knowledge of technology.

In the late 1920s and 1930s, the period of Stalin’s five-year plans, the Constructivists suffered from the increasingly centralized control of art in Russia that led to the eventual imposition of Socialist Realism. They continued, however, to be particularly active in typographical, poster and exhibition design, areas in which photomontage was seen as an effective propaganda weapon (e.g. Klucis’s We Will Repay the Coal Debt to the Country, 1930; and Lissitzky’s design for the Pressa exhibition in Cologne, 1928; see Lodder, plate XV and figs 6.13a–b and 6.14). In 1931 Klucis stated, ‘One must not think that photomontage is merely the expressive composition of photographs. It always includes a political slogan, colour and purely graphic elements. The ideologically and artistically expressive organization of these elements can be achieved only by a completely new kind of artist—the constructor’ (1990 exh. cat., p. 116). Nevertheless, in an increasingly repressive political climate, official requirements for potent propaganda imagery tended to take priority over compositional invention, as is evident from issues of the internationally disseminated USSR in Construction that Rodchenko and Lissitzky designed in the later 1930s (e.g. by Lissitzky: USSR im Bau, No. 9, 1933). Constructivism may have been inspired by the early idealism of the Revolution, but it subsequently fell victim to the actual political system that emerged.

See also Russia,§III, 3.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

© Oxford University Press 2007

How to cite Grove Art Online

Animal Farm

wikipedia page here and HTML version of the book here

Quotes:

Chapter 1:

Chapter 3:

Chapter 7:

Chapter 10: ALL ANIMALS ARE EQUAL

BUT SOME ANIMALS ARE MORE EQUAL THAN OTHERS.

Animal Farm: A Fairy Story is a novel by George Orwell, and is regarded in the literary field as one of the most famous satirical allegories of Soviet totalitarianism. Orwell based major events in the book on novels from the Soviet Union during the Stalin era. Orwell, a democratic socialist, and a member of the Independent Labour Party for many years, was a critic of Stalin, and was suspicious of Moscow-directed Stalinism after his experiences in the Spanish Civil War.

Quotes:

Chapter 1:

No animal shall kill any other animal. All animals are equal.(part of the original seven commandments) -

Chapter 3:

Squealer: "Comrades!" he cried. "You do not imagine, I hope, that we pigs are doing this in a spirit of selfishness and privilege? Many of us actually dislike milk and apples. Milk and apples (this has been proved by Science, comrades) contain substances absolutely necessary to the well-being of a pig. We pigs are brainworkers. The whole management and organization of this farm depend on us. Day and night we are watching over your welfare. It is for your sake that we drink that milk and eat those apples."

Chapter 7:

But when Muriel reads the writing on the barn wall to Clover, interestingly, the words are, "No animal shall kill any other animal without cause."

Chapter 10: ALL ANIMALS ARE EQUAL

BUT SOME ANIMALS ARE MORE EQUAL THAN OTHERS.

Animal Farm: A Fairy Story is a novel by George Orwell, and is regarded in the literary field as one of the most famous satirical allegories of Soviet totalitarianism. Orwell based major events in the book on novels from the Soviet Union during the Stalin era. Orwell, a democratic socialist, and a member of the Independent Labour Party for many years, was a critic of Stalin, and was suspicious of Moscow-directed Stalinism after his experiences in the Spanish Civil War.

Why Must Nina's Soul be poisoned by Yoghurt?

Why must Nina's soul be poisoned by yoghurt?

Sean O'Hagan

Sunday April 8, 2007

The Observer

I'm having a Nina Simone moment. Last week, while visiting a friend whose iPod is permanently set to 'shuffle', I was caught unawares by her version of Dylan's 'Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues'. I had not heard the song in a while and it's drowsy, jazzy swirl took me by surprise all over again. I went home and dug out all her old records and I've been immersed ever since.

That's when I realised I have one problem with Nina Simone right now, a problem I would not have had, say, five years ago. A problem that has nothing to do with Nina per se. It concerns the provenance - and the meaning - of one of her best-known and stirring songs, a song from that troubled time when she, like many black artists, embraced the cause of civil rights. In the late Sixties, she wrote the anthemic 'Young, Gifted and Black' and the angry 'Mississippi Goddam'. She sang the stirring 'Backlash Blues', written by her friend, author Langston Hughes, and turned another song, 'Ain't Got No/I Got Life', originally written for Hair, into a stirring celebration of black pride and defiance.

The latter song was not strictly hers, but as soon as she sang it, she claimed it. If you doubt this, click on YouTube and witness her performance at the Harlem Music Festival in 1969. It is one of those heartstopping moments that YouTube was made for, a slice of musical history, but, more important, a glimpse of a time when a song could really mean something, could carry the weight of a people's hopes and dreams, its aspirations and anger. A time, too, when a singer could echo the activism of the streets, could galvanise the consciousness-raising radicalism of an era. Nearly 40 years on, that song is being used in a TV ad to sell yoghurt.

Sean O'Hagan

Sunday April 8, 2007

The Observer

I'm having a Nina Simone moment. Last week, while visiting a friend whose iPod is permanently set to 'shuffle', I was caught unawares by her version of Dylan's 'Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues'. I had not heard the song in a while and it's drowsy, jazzy swirl took me by surprise all over again. I went home and dug out all her old records and I've been immersed ever since.

That's when I realised I have one problem with Nina Simone right now, a problem I would not have had, say, five years ago. A problem that has nothing to do with Nina per se. It concerns the provenance - and the meaning - of one of her best-known and stirring songs, a song from that troubled time when she, like many black artists, embraced the cause of civil rights. In the late Sixties, she wrote the anthemic 'Young, Gifted and Black' and the angry 'Mississippi Goddam'. She sang the stirring 'Backlash Blues', written by her friend, author Langston Hughes, and turned another song, 'Ain't Got No/I Got Life', originally written for Hair, into a stirring celebration of black pride and defiance.

The latter song was not strictly hers, but as soon as she sang it, she claimed it. If you doubt this, click on YouTube and witness her performance at the Harlem Music Festival in 1969. It is one of those heartstopping moments that YouTube was made for, a slice of musical history, but, more important, a glimpse of a time when a song could really mean something, could carry the weight of a people's hopes and dreams, its aspirations and anger. A time, too, when a singer could echo the activism of the streets, could galvanise the consciousness-raising radicalism of an era. Nearly 40 years on, that song is being used in a TV ad to sell yoghurt.

Monday, 9 April 2007

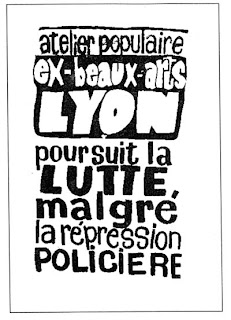

Atelier Populaire & Quotes

La Lutte Continue

“The posters produced by the ATELIER POPULAIRE are weapons in the service of the struggle and are an inseparable part of it. Their rightful place is in the centers of conflict, that is to say, in the streets and on the walls of the Factories. To use them for decorative purposes, to display them in bourgeois places of culture or to consider them as objects of aesthetic interest is to impair both their function and their effect. This is why the ATELIER POPULAIRE has always refused to put them on sale. Even to keep them as historical evidence of a certain stage in the struggle is a betrayal, for the struggle itself is of such primary importance that the position of an ‘outside’ observer is a fiction which inevitably plays into the hands of the Ruling Class. That is why these works should not be taken as the final outcome of an experience, but as an inducement for finding, though contact with the masses, new levels of action, both on the cultural and the political plane.”

Statement by the Atelier Populaire, Paris, 1968.

QUOTE: from Design Literacy (Second Edition) p31

The Paris student revolution of May 1968 was one of the most dramatic political events in a decade noted for it's tumult. In a modern-day storming of the Bastille, a coalition of more than ten million students and workers mounted the barricades to protest Charles de Gaule's aging conservative government. By the end of the year the nation was paralyzed by strikes and demonstrations. In contrast to the social protest concurrently hitting many nations, this whirlwind insurgency actually shook the system, provoking substantive though temporary concessions.

Intellectuals and workers were brought to the battlements by their shared interest in social reform and by their indignation at the repression - most aggressively represented by the paramilitary National Police who were brought in to squelch the protests through violence. Both groups were further induced by the daily barrage of critical posters designed by the Atelier Populaire to inform and mobilize the populace. This group of disparate painters, graphic artists, and art students produced hundreds of iconic, one-colour, brush-and-ink posters that were pasted all over Paris and became an indelible symbol of the popular uprising. In keeping with the character of collectivism, these paper bullets were unsigned by any individual.

My Refections

In my opinion there will always be a role for art in revolutions. There are the "fine" arts, and there are communication or "practical / commercial" arts. My interest is primarily in the latter, as I have no wish to be a poor starving artist for the rest of my life.

Communication art is primarily about communication. It is used to sell things, advertise, communication, broadcast. It is obvious that this is probably the primary means used for revolutionary propaganda, just as it would be used for a party political broadcast or an advertisment for the new generation of Apple iPod.

Such communication artists will have undoubtably have had to do an amount of work which they may not ideally wanted to do in order to survive, whether this be design for huge corporations, political parties, revolutionaries (the archetypal unethical "Bad-man") in order to survive. There is undoubtedy the case that some of these artists may have beleived what they were doing, or in the process of subverting the public, were then in turn subverted too.

Communication art is primarily about communication. It is used to sell things, advertise, communication, broadcast. It is obvious that this is probably the primary means used for revolutionary propaganda, just as it would be used for a party political broadcast or an advertisment for the new generation of Apple iPod.

Such communication artists will have undoubtably have had to do an amount of work which they may not ideally wanted to do in order to survive, whether this be design for huge corporations, political parties, revolutionaries (the archetypal unethical "Bad-man") in order to survive. There is undoubtedy the case that some of these artists may have beleived what they were doing, or in the process of subverting the public, were then in turn subverted too.

Situating El Lissitzky; Quotes

"Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge" (1920) - agriprop - although probably too abstarct for many of the public.

Quotes:

Without question, the role of the propaganda publication was less the winning of new converts than it was the affirmation of belief and loyalty of the elect, among whom, of course were the artists themselves. This closed system aligned neatly with the fusion of experiential levels suggested by the designs of 1934 and 1935: the merging of author, subject, and reader into one vector of enthusiastic approval of the Soviet Union and its glories.

Peter Nisbet Essay p228

Let me sum up. First, with regard to agitprop. I believe we are not doing all we could in this area, and I think I should set out the tasks we need to assign to Glavpolitput and Tsekprofsozh. We shall not be able to manage without cooperation from the trade unions.Glavpolitput and Tsekprofsozh ought to start straight away organizing agitation about work on the railroads the railroads and the fight against labour deserters. We need to organize this fight with the help of posters - popular ones - which will show the deserters as the criminals they are. These posters should eb hanging in every workshop, every department, every office. Right now transportation is the the lynchpin. And therefore there should not be a single theatre, a single public spectacle, a single movie-show, where people are not reminded of the harmful role of the labour deserter. Wherever the railroad worker goes, he should find a poster which mocks the deserter and puts the shirker [progul'shchik] to shame.... We need to use gramophones for agitation purposes. Posters are all very well for the city, in the village they are not much use. Let us make ten or so records against shirking and desertion. Lists of deserters should be printed and circulated. Even if we do not get the deserters back by these means, at least we shall shame and frighten anyone who is leaning in that direction.... Besides, we have to instill the awareness that labour conscription (part of Trotsky's general dream at this time of the militarization of the economy) means staying at one's post as long as the circumstances demanded it.... The courts should likewise be a might engine of agitation and propaganda. Their role is not only to mete out punishment to the guilty but also to agitate by means of repression. We should organize a show trial (literally, a loud trail) of one or two doctors who give out phony certificates.... If we put the trial on in a theatre in one of the cities and invite representatives from all the workshops, and have the trial reported in all the papers and broadcast on the radio - that will really do some educational work.

Leon Trotsky, Khooviastvennoe stroitelstvo respubliki (Moscow: Gosizdat, 1927) 374-76. See the discussion of the speech in William H. Cahmberlin, The Russian Revolution, 1917-1921 (new York: Macmillan, 1935 reprint, New york: Macmillan, 1952), 2:294.

Themes

Situationalists - Student Riots Paris 1968

more here

Guy Debord obituary here url: http://catless.ncl.ac.uk/Obituary/debord.html

Check Design Literacy - Steven Heller. Grapus

Ideas: Revolutions are initially subversive, but then there is the following counter revolution. This was the case with the Russian Revolution, which started as a peoples revolution, but over time the people were supressed by Stalin.

Revolution - A metaphor: George Orwell “Animal Farm”

more here

Guy Debord obituary here url: http://catless.ncl.ac.uk/Obituary/debord.html

Check Design Literacy - Steven Heller. Grapus

Ideas: Revolutions are initially subversive, but then there is the following counter revolution. This was the case with the Russian Revolution, which started as a peoples revolution, but over time the people were supressed by Stalin.

Revolution - A metaphor: George Orwell “Animal Farm”

Ideas and Notes

There are parallels between revolutionary propaganda and advertising: both sell dissatisfaction.

Here's something you didn't know you want, but you do now.

The Globalisation of brands, or rather global brands (No Logo makes the distinction between brands that attempt to integrate to different cultures around the world, and “global” brands that simply sell the same brand around the world (McDonalds).

Here's something you didn't know you want, but you do now.

The Globalisation of brands, or rather global brands (No Logo makes the distinction between brands that attempt to integrate to different cultures around the world, and “global” brands that simply sell the same brand around the world (McDonalds).

Sunday, 8 April 2007

Simon Robson

Simon Robson made his name from his short animated graphic thesis “What Barry Says”. The subject was about the U.S. War on terror and far-right politics of the bush administration. Simon's next pieces were for Nike.

http://www.knife-party.net/flash/barry.html

http://www.knife-party.net/movs/ni_quicktime.htm

The intention here is to show that global corporations such as Nike always use cutting edge artists to keep their brands cool. Almost every good motion designer i look at will have done these huge brands (Nike, Coca Cola, McDonalds, MTV) amongst their own personal work.

No Logo Quotes

In 1974, Norman Mailer described the paint sprayed by urban graffiti artists as artillery fired in a war between the street and the establishment.“You hit your name and maybe something in the whole scheme of the system gives a death rattle. For now your name is over their name... your presence is on their presence, your alias hangs over their scene.”Norman Mailer, “The Faith of Graffiti” Esquire, May 1974, 77 Twenty-five years later, a complete inversion of this relationship has taken place. Gathering tips from the graffiti artists of old, the superbrands have tagged everyone - including the graffiti writers themselves. No space has been left unbranded.

No Logo p73

China

All in all, the so-called global teen demographic is estimated at one billion, and these teenagers consume a disproportionate share of their families' incomes. In China, for instance, conspicuous consumption for all members of the household remains largely unrealistic. But, argue the market researchers, the Chinese make enormous sacrifices for the young - particularly for young boys - a cultural value that spells great news for cell-phone and sneaker companies. Laurie Klein of Just Kid Inc., a U.S. firm that conducted a consumer study on Chinese teens, found that while Mom, Dad and both grandparents may do without electricity, their only son (thanks to the country's one-child policy) frequently enjoys what is widely known as “little emperor syndrome,” or what she calls the “4-2-1” phenomenon: four elders and two parents scrimp and save so the one child can be an MTV clone. “When you have the two parents and four grandparents spending on one child, it's a no-brainer to know that this is the right market,” says one venture capitalist in China.

“Western Companies Compete to Win Business of Chinese Babies,” Wall Street Journal, May 15th, 1998. The quotation comes from Robert Lipson, president of U.S.-China Industrial Exchange Inc.

Furthermore, since kids are more culturally absorbent than their parents, they often become their families dedicated shoppers, even for big household items. Taken together, what this research shows is that while adults may still harbor traditional customs and ways, global teens shed those pesky national hang-ups like last year's fashions. “They prefer Coke to tea, Nikes to sandals, Chicken McNuggets to rice, credit cards to cash,” Joseph Quinlan, senior economist at Dean Witter Reynolds Inc. told The Wall Street Journal.

The message is clear: get the kids and you've got the whole family and the future market.

p118, 119

The Branding of Music

In 1993, the Gap launched its “Who wore khakis?” ads, featuring old photographs of such counterculture figures as James Dean and Jack Kerouac in beige pants. The campaign was in the cookie-cutter co-opation formula: take a cool artist, associate that mystique with your brand, hope it wears off and makes you cool too. It sparked the usual debates about the mass marketing of rebellion, just as William Burroughs's presence in a Nike as did at around the same time.

Fast forward to 1998. The Gap launches its breakthrough Khakis Swing ads: a simple exuberant miniature music video set to “Jump, Jive 'n' Wail” - and a great video at that. The question of whether these ads were "co-opting" the artistic integrity of the music was entirely meaningless. The Gap's commercials didn't capitalize on the retro swing revival - a solid argument can be made that they caused the swing revival. A few months later, when singer-songwriter Rufus Wainwright appeared in a Christmas-themed Gap ad, his sales soared, so much so that his record company began promoting him as “the guy in the Gap ads.” Macy Gray, the new R&B “It Girl”, also got her big break in a Baby Gap ad. And rather than the Gap Khaki ads looking like rip-offs of MTV videos, it seemed that overnight, every video on MTV - from Brandy to Britney Spears and the Backstreet Boys - looked like a Gap ad; the company has pioneered it own aesthetic, which spilled out into music, other advertisements, even films like The Matrix. After five years of intense lifestyle branding, the Gap, it has become clear, is as much in the culture-creation business as the artists in it's ads.

p45

Culture Jamming / Situationists

It was Guy Debord and the situationists, the muses and theorists of the theatrical student uprising of Paris, May 1968, who first articulated the power of a simple detournment, defined as an image, message or artifact lifted out of its context to create a new meaning. But though culture jammers borrow liberally from the avant-garde art movements of the past - from Dada and Surrealism to Conceptualism and Situationism - the canvas these art revolutionaries were attacking tended to be the art world and its passive culture of spectatorship, as well as the anti-pleasure ethos of mainstream capitalist society. For many French Students in the late sixties, the enemy was the rigidity and conformity of the Company Man; the company itself markedly less engaging. So where Situationist Asger Jorn hureled paint at pastoral paintings bought at Flea markets, today's culture jammers prefer to hack into corporate advertising and other avenues of corporate speech. And if the culture jammers' messages are more pointedly political than their predecessors', that may be because what were indeed subversive messages in the sixties - “Never Work,” “It Is Forbidden to Forbid,” “Take Your Desires for Reality” - now sound more like Sprite or Nike slogans; Just Feel It. And the "situations" or "happenings" staged by the political pranksters in 1968, though genuinely shocking and disruptive at the time, are the Absolut Vodka ad of 1998 - the one featuring purple-clad art students storming bars and restaurants banging on bottles.

p282, 283

Saturday, 7 April 2007

Bibliography

Klein, N. (2000), No Logo. London. Flamingo.

Perloff, N., Reed, B. (2003), Situating El Lissitzky. Los Angeles. Getty Publications.

Rickey, G. (1967), Consructivism - Origins and Evolution. London. Studio Vista Ltd.

http://www.knife-party.net/flash/barry.html

http://www.knife-party.net/movs/ni_quicktime.htm

Leon Trotsky, Khooviastvennoe stroitelstvo respubliki (Moscow: Gosizdat, 1927) 374-76. See the discussion of the speech in William H. Cahmberlin, The Russian Revolution, 1917-1921 (new York: Macmillan, 1935 reprint, New york: Macmillan, 1952), 2:294.

Heller, S. Design Literacy (Second Edition). 2004. New York. Allworth Press P31-33

Weston, R. (1996, RP 2005), Modernism. London. Phaidon Press Limited.

O'Hagen, S. The Observer 08/04/07 - http://media.guardian.co.uk/advertising/comment/0,,2052268,00.html

Orwell, G. Animal Farm: A Fairy Story (1945) London. Penguin Books Ltd; New Ed edition (3 Sep 1998)

Chambers 20th Century dictionary 2003.

Hughes, R. (1980, rp. 1991). The Shock of the New New York. Columbus, Ohio. McGraw Hill.

Trotsky, L. (1938). See Trotsky (1950).

Trotsky, L. (1950). “Art and Politics in Our Epoch”, Fourth International Vol. 11, No. 2 pp. 61-64.

Tulard,J., Fayard, J-F and Fierro, A. (1987) Histoire et dictionnaire de la Révolution française, 1789–1799.

Paris.

Woods, A. and Grant, T. (2000). Lenin and Trotsky: What They Really Stood for. London, WellRed.

Woods, A. (2000).http://www.Trotsky.net/Trotsky_year/Marxism_and_art.html

http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/delacroix/liberte/

http://www.bpi1700.org.uk/printsMonths/august2006.html

http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~vbonnell/images/malevich.jpg

http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~vbonnell/images/udarnuiu_uborku.jpg

http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~vbonnell/images/o_kazhdom.jpg

Perloff, N., Reed, B. (2003), Situating El Lissitzky. Los Angeles. Getty Publications.

Rickey, G. (1967), Consructivism - Origins and Evolution. London. Studio Vista Ltd.

http://www.knife-party.net/flash/barry.html

http://www.knife-party.net/movs/ni_quicktime.htm

Leon Trotsky, Khooviastvennoe stroitelstvo respubliki (Moscow: Gosizdat, 1927) 374-76. See the discussion of the speech in William H. Cahmberlin, The Russian Revolution, 1917-1921 (new York: Macmillan, 1935 reprint, New york: Macmillan, 1952), 2:294.

Heller, S. Design Literacy (Second Edition). 2004. New York. Allworth Press P31-33

Weston, R. (1996, RP 2005), Modernism. London. Phaidon Press Limited.

O'Hagen, S. The Observer 08/04/07 - http://media.guardian.co.uk/advertising/comment/0,,2052268,00.html

Orwell, G. Animal Farm: A Fairy Story (1945) London. Penguin Books Ltd; New Ed edition (3 Sep 1998)

Chambers 20th Century dictionary 2003.

Hughes, R. (1980, rp. 1991). The Shock of the New New York. Columbus, Ohio. McGraw Hill.

Trotsky, L. (1938). See Trotsky (1950).

Trotsky, L. (1950). “Art and Politics in Our Epoch”, Fourth International Vol. 11, No. 2 pp. 61-64.

Tulard,J., Fayard, J-F and Fierro, A. (1987) Histoire et dictionnaire de la Révolution française, 1789–1799.

Paris.

Woods, A. and Grant, T. (2000). Lenin and Trotsky: What They Really Stood for. London, WellRed.

Woods, A. (2000).http://www.Trotsky.net/Trotsky_year/Marxism_and_art.html

http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/delacroix/liberte/

http://www.bpi1700.org.uk/printsMonths/august2006.html

http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~vbonnell/images/malevich.jpg

http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~vbonnell/images/udarnuiu_uborku.jpg

http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~vbonnell/images/o_kazhdom.jpg

Saturday, 3 March 2007

Critical Studies

This blog is where I will be organising my research for my critical studies essays. The first essay, the review pieces were done at Christmas, and at that time i had a load of paperwork that I had to organise and carry about, so it became obvious that a blog would be a great organisational tool.

The next assignment comprises of three different questions, and we are to pick one. They all look interesting, and I think I would learn from doing any of them, so this one ought to keep me busy:

NB - THIS IS THE QUESTION

In response to the following statement by Robert Hughes discuss how art has been used in support of revolutions. You may wish to focus on the idea of the monument, or propaganda in relation to your subject or related fields of art and design.

Like the French revolutionaries before them, Lenin and Lunacharsky believed in propaganda-by-monument…His [Lenin] taste was far more conservative than Lunacharsky’s, and he did not want to be commemorated as “a Futurist scarecrow”;” but the very idea of “monumental” art was reinvented in Russia under his aegis. No state had ever set down its ideals with such radically abstract images, and that they were not actually built is less significant than that they were imagined. Reality was against them: Russia had no spare bronze, steel, or manpower. Artists were therefore employed on more immediate Agitprop jobs that have mostly perished – posters, street theatre floats, and parade décor. They designed and distributed, through the Soviet propaganda system, thousands of crude, memorable ROSTA posters. Printed in bright Image d’Epinal colours on cheap paper…They also took control of the Russian art schools, those incubators of future form. Thus in 1918 the school at Vitebsk was headed by Marc Chagall, and its staff included Malevich and El Lissitzky. Lunacharsky…created the Higher State Art Training Centre or Vkhutemas School of Moscow. It turned into the Bauhaus of Russia, the most advanced art college anywhere in the world, and the ideological centre of Russian Constructivism. (Hughes 1980 rp 1991:87)

Hughes, Robert (1980 rp 1991) The Shock of the New New York: McGraw-Hill

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)